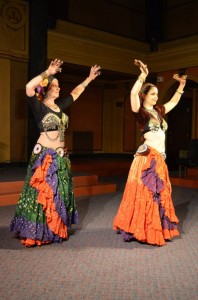

As readers of my blog know, I’m thoroughly in love with American Tribal Style® Belly Dance (ATS for short). I’ve written about why it’s interesting from a folklore studies perspective, how its unique fractal structure makes it distinct from other belly dance styles, and how it helps address cultural appropriation issues by veering sideways of the debate and not trying to be authentic. I’m also – cards on the table – a certified ATS instructor and a Sister Studio to FatChance BellyDance® (the creators of the style).

So if ATS was created in the 1980s as an improvisational belly dance format by FatChance, and has since become a standardized dance language worldwide, what’s ITS?

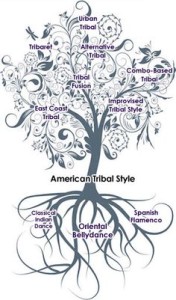

ITS stands for Improvisational Tribal Style, and it refers to the multiple dance languages and dialects that have emerged from ATS and evolved into their own improvisational dance cue systems. The language metaphor remains useful, since just like languages, we can look at tribal style improv as a series of historically interconnected communication systems. Some of them are mutually intelligible, and others are not.

The tribal belly dance family tree pictured here reminds me of the charts we used in the historical linguistics class I took at Berkeley. There’s a clear sense of lineage, influence, and ancestry.*

So with ITS, you end up with this rather fascinating case study of interrelated dance forms that have become immensely popular worldwide. I could list my favorite examples of ITS sub-styles for days, but instead I’ll get to my main point:

ATS is to ITS as Impressionism is to Neo-Impressionism

What do I mean by that? If you’re an art history nerd like me, you’ll know that Impressionism started in the 1870s as an artistic movement that related to light and color differently than was then in vogue. About a decade after the start of Impressionism, a related movement called Neo-Impressionism took off, altering the aims of Impressionism but still definitely borrowing from the movement’s momentum and techniques. And then, depending on who you ask, there was the Post-Impressionist movement, which referred to a lot of the same artists as the Neo-Impressionist title, but also might’ve been more of a time period than a coherent movement.

Anyway, we could linger on the details, but the main part of the metaphor that I want to access is this: ATS is like the Impressionism of the contemporary belly dance scene, since its arrival shook things up and laid the groundwork for other types of innovation in the belly dance world. ITS built on the developments of ATS, pushing farther in some ways and recursing in others.

My problem is this: when I talk to someone who’s into ITS who doesn’t know a thing about ATS, it’s hard for me to wrap my brain around. It’s like talking to someone who’s nuts about Seurat and is trying to paint in his style, but has never heard of Monet.

Maybe it’s because I’ve always been a nerd about history, but that makes me go WTF. Know your dance history, folks! Not only does it make performances more visually interesting when you can trace the evolution of movements over time, but it also helps us understand where we fit in the ever-changing dance world. How much are we bound by tradition, and where does creativity fit into the particular genre of dance we’ve chosen to explore? What kinds of artistry are most available to us? I’m not trying to be snotty about how ATS “came first” and thus is more legit; as I’ve blogged about, I don’t really care about the origins of cultural phenomena because there are so many other questions that are more interesting to me.

For me, understanding where things come from (as far back as we can feasibly determine, anyway) and how they’ve changed over time deepens my appreciation of them. And as someone who practices this art form, I think it’s an important way to show respect, sorta like a “know the rules before you break them” attitude when it comes to the act of creation (not that I’m advocating breaking any rules here).

As always, I love feedback and would enjoy hearing other dancers’ thoughts on this metaphor.

*Hungry for more tribal dance tidbits? Deep Roots Dance has collected an excellent sampling of links about the history of tribal belly dance.