As both an academic and an artist (wow, how many blog posts have I written/will I write that start off like this?), I’ve noticed that having a fine-tuned critical gaze is very important and useful, but it also has its downsides.

On the academic side, my ability to critique works and ideas has been a great help. Having a critical gaze helps me sift through scholarship when I’m doing background research for a new project or syllabus. I’m a thorough editor, and I actually enjoy proof-reading papers (excepting my own). While I’m not a specialist in rhetoric, I’ve gotten better at identifying the various types of arguments that one can make in an academic paper or book, as well as the sorts of evidence that are appropriate and compelling to present.

In terms of the arts, I’ve become excellent at identifying technical flaws in dance performances. I suspect this is partly because I’ve taught dance for a number of years so I’m proficient at picking out typical beginner mistakes (such as not having proper posture, which is the foundation of everything we do in American Tribal Style® belly dance), and partly because I’ve simply watched a ton of dance performances. I mean, I’ve been dancing for almost half my life, and most of that at a semi-professional if not professional level. I’d be a little worried if my eyes weren’t catching mistakes and spotting places where a dancer could improve.

But being good at critiquing someone or something, and then actually implementing the critique, are two separate things. Few people like to be told that they’re doing something wrong, and those that do, tend to need to be in the right context to hear it. If someone sets foot in a dance classroom or a conference presentation, then yes, they’re probably open to hearing what could be improved. But even then, it’s a bit of a gamble as to how a critique will be received. Even well-intention critiques (and I like to think that mine always are) can feel devastating.

And then there’s this issue: critiquing something is not the same as creating something. The latter is frequently more involved and time-consuming, and one tends to put pieces of one’s heart or oneself into a creation, whether a choreography for a performance or an academic article.

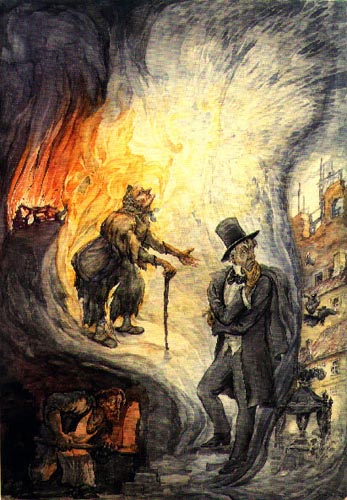

I’ve written about Hans Christian Andersen’s views on art here, and I’d like to return to Andersen to explore his views on critics. As you might guess about an egotistical artist who was also largely unhappy with his life, he wasn’t a fan of critics. He made his views known in his stories, including two that I’ll mention here.

In a story titled “‘Something,'” five brothers set out to do something useful in the world. One becomes a builder, another an architect, and so on. However, the fifth brother declares: “I see that none of you will ever become something, even though you all think you will….I want to stand apart. I will contemplate and criticize what you do. There is always something wrong with anything man makes. I shall point it out so all can see it. That is something!” (Hans Christian Andersen: The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories, trans. Erik Christian Haugaard, 540).

And indeed, people began to praise the fifth brother: “He is really something. He has got a good head on his shoulders and can make something into nothing.” (ibid 540). However, when the fifth brother tries to get into heaven, he can’t produce evidence that he’s done a single good deed in his lifetime. In fact, the best thing he can do is keep his mouth shut instead of offering his opinion – and that, we’re told, is “something.”

In another story, “A Question of Imagination,” a young man who wants to be a writer goes to ask an old woman for help coming up with ideas for what to write about (because everything has already been written about – and goodness, if people were thinking that in the 1800s, imagine how dire the situation must be now!). However, no matter how much inspiration the old woman tries to feed the boy, he remains oblivious to the wonders of the world around him. Finally, the woman tells him to become a critic. He “followed her advice. He became an expert at looking down his nose at poets because he couldn’t become one himself.” (Hans Christian Andersen: The Complete Fairy Tales and Stories, trans. Erik Christian Haugaard, 974).

There’s something tragic, Andersen implies, about the person who cannot create but can only critique. However, I’d argue instead that critique doesn’t in and of itself signal a lack; instead, I think it’s critique without compassion that’s the problem. If the critic is also a creator, then hopefully she will have some understanding what goes on in the artistic process, and won’t be snide or cruel in her critique. I’d hope that critics who aren’t also creators, but are simply quite good at what they do, would also have some compassion for artists and not be unduly destructive or negative.

I’m not implying that we’d suddenly live in a utopian world without hurtful negative feedback if everyone made an effort to be a little more compassionate. Haters gonna hate, and all that. I do think, however, the critics should evaluate their relationships with the materials they critique, and be honest with themselves (and the world) about their reasons for doing so. That’d be a start, anyway.