If you haven’t already, go read my post on flow vs. tech to get a sense of the terms I’m using here to describe how my experience of the flow arts is evolving.

As much as I love to get technical with belly dancing, I have this weird relationship with tech in the flow arts world, and I recently figured out part of why that is.

See, I’m a slow learner sometimes, and I need certain learning environments to succeed. I aced AP Calculus in high school and got a 5 on the AP exam (the highest possible score), but stopped taking math and science classes in college, because I knew that I wouldn’t do well in a class of 600 cut-throat pre-med students. Give me texts, narratives, and theories thereon, and I will rock out learning by myself, in small groups, in big groups, in practically any context. But specific things – like Foucault – also just take me longer to learn, and I’m trying not to shame myself for that.

It turns out that technical movements that are far outside my realm of experience fall into the overlapping categories of “takes me a while to learn” and “need to learn in a hands-on, small, learner-focused setting.”

This was an interesting realization to come to, because by participating in the flow arts world through hoopdance, firedance, and fan dancing, I’ve had to navigate the flow vs. tech divide in order to discover what works for me. I’ve taken tech-oriented workshops and classes and been frustrated to the point of tears and quitting, and subsequently realized that I’ve had to give myself more space and compassion before approaching tech topics at all. It’s not because I’m too stupid to learn the concepts – like what makes an antispin flower or a triqueta – but rather, I have a learning process that’s unique to me, and doesn’t always mesh well with highly technical concepts in large, depersonalized learning environments.

I’m not interested in criticizing tech-oriented teachers for not doing a good enough job of teaching their material in a way that minimizes shame because that’s not what’s going on here; even in really supportive learning environments, I’ve experienced shame because of when my body has quit on me. Rather, I’d like to describe how I came to eventually value tech as a necessary component to my flow.

This is not a new idea: most dancers and movement artists acknowledge that you need a baseline layer of technique (regardless of how complicated or “techy” it is) in order to be able to construct a practice and, well, have something to practice in it. You need moves or techniques to string together and drill so that you can work on flowing smoothly between them.

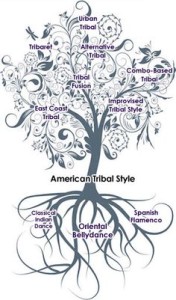

But I’ve been resistant to tech in the flow arts in a way that’s been somewhat confounding. In belly dance, I’ll do tech all day if it means a chance to work on my American Tribal Style® skills and thus do improvisational dancing (as seen in this performance wherein I dance with my troupe), or if it means I can bust out some neat muscle isolations in layered combinations that are challenging and visually interesting (as here, in a solo that I really enjoyed putting together). While my ATS® dancing and my solo dancing each incorporate slightly different skills from the belly dance toolbox, both are quite technical in nature and requires lots of drilling to become competent.

So it’s not that I’m incapable of learning tech, since I’ve clearly managed it with belly dance. I think, instead, that with the flow arts, and hoopdance in particular, tech is rarely interesting in and of itself. I just don’t care about fancy, complex moves if they aren’t also visually appealing, dramatic, expressive, or otherwise a means to an end of dancing creatively, putting on a compelling performance, or getting into a flow state. Yes, I know that any technique, once learned well, can be an entrance to flowing. But it takes me longer to get there with the flow arts than with belly dance, for whatever reason.

What it boils down to for me is this: when you prioritize flow over tech, as I have with my flow arts, there is no prescribed route or path to success. The destination is you: your experiences, your satisfaction, your own unique learning process. When flow is your goal, your body and your creativity will tell you which paths to explore, and will guide you in getting there. Attuning to flow is an experience of deep listening to your body and your process, which can be difficult at first, since I doubt there are many things in contemporary American culture that encourage the same dance of movement and stillness that it takes to tune in. It’s really rewarding, though. I spent my first few years hooping focusing solely on flow, and only in the last year or two starting to learn tech and tricks. This runs counter to what you see a lot of other hoopers doing, but I’m accustomed to being the odd one out.

Focusing on flow rather than tech – or rather, letting flow guide my process, and help me figure out when to incorporate tech – has been a really fruitful approach for me. It helps me create performances like this one, to Unwoman’s cover of “Take Me to Church”, where I’m really focused on improvising and expressing, rather than fitting in techy tricks. I know my hooping style will continue to evolve, but I really love where I’m at, slowly dipping a toe into tech, but still letting flow be my teacher.

I love dissecting and discussing artistic processes in general, and I’m curious to hear what others think. How does flow help you find yourself? How do you decide when to focus on flow vs. tech? What’s your process?