I am a teacher, scholar, feminist and performer (among the other identities I shift in and out of). One of the common threads that runs through all these roles is the desire, and even the necessity, to critique and thus transform. But when you’re critiquing someone’s dancing, someone’s writing, or someone’s political stance, how do you go about it positively, in a way that makes people receptive to it (or at least doesn’t turn them off from the very first words you say)?

One dancer I respect told me that she always praises a dance student before going on to offer criticism (as in, “That was a beautiful shimmy! Now make sure you stay in posture and hold your arms at shoulder height”). That helps a student be ready to receive the criticism and take it to heart in the way it was meant: as a tool to aid in growth and progress, rather than as an insult or an attempt to take someone down a notch.

At conferences, if I see a paper I really don’t like because I think the scholar doesn’t know what she’s talking about, I try to open with something nice before I go on to my criticism (for instance, “I thought your connection between X and Y tale types was really clever. However, I think you may be a bit off base in focusing on the origins of motifs that we can’t verify with empirical research…”). Not that it always works; I’ve had people go into rude-defensive mode, but at least I tried.

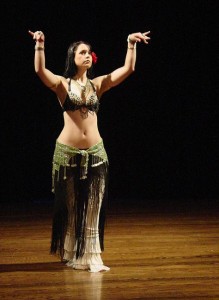

As a feminist, I’m aware that it can take a lot of positive reinforcement to reach a woman through the layer of negativity that we tend to accrue in our culture. Sometimes it takes a while to get someone to accept a compliment—and I mean truly accept it, not just smile and nod while thinking “But I’m actually still doing the whole move wrong, and I’m fat, and I’m not as young as the other girls in the class.” This is unfortunate, and I’m hoping that creating more safe spaces for women to, for instance, take up belly dancing for the sheer joy of it will help.

I wasn’t always this way; people who have danced with me know that I tend to be extremely critical of myself and of others. But I mean it in the best possible way; I assume that everyone is as ruthlessly disciplined and intent on self-improvement as I am. I’ve since learned that this is not true, and that not everyone wants to hear about every little thing they did wrong in a choreography, or every little thing I think could’ve been better in an essay. I still think that my ability to be incisively critical is one of my strengths, since I have a highly trained eye when it comes to both intellectual and aesthetic pursuits, but I’ve learned to keep a lot of my thoughts to myself unless asked to share. I’ve seen, firsthand, how important it is to boost people up before you tear them down (or act in such a way that they perceive it like that). I’m stubborn so it took a while for me to recognize this, but I’m here now. And I also, along the same lines, try not to say anything unless I have something nice to say, which is hard since I tend to be blunt, but oh well.

So now, because I truly believe that it’s both important and effective to offer creative, positive, or constructive comments/suggestions before moving into the negative, destructive, or super-critical stuff, I’m figuring out how to implement it in the rest of my life.

For example, as a pro-choice, sex-positive feminist, I am not thrilled with how so many American religious conservatives want to not only outlaw abortion but try to restrict access to birth control and sex education. This, when our country can’t even seem to take care of the children that already exist: malnutrition, poor literacy, and other physical and social health issues plague our young. So… why not address this issue (the constructive part) before trying to take away people’s choices and access (the destructive part)? I mean, why not throw all those resources into trying to help the needy citizens of our country instead of legislating against, shaming, and sometimes even committing acts of violence against the people who provide access to and obtain abortions and birth control?

That is the political feminist portion of this post, and I know that not everyone will agree with me here (for instance, you could argue that saving the life of a fetus is a more constructive act than trying to help an impoverished child, prisoner, or mentally ill person, though I’m not quite sure how that logic prioritizes a not-yet life over an existing life). But what I hope people get out of this post is the will to reexamine your rhetoric, intentions, and actions when you interact with people. Could you go about something more constructively or creatively at first? Could you do something to inspire confidence in someone rather than insecurity?

(fyi, I was tempted to make a bunch of jokes about constructionism vs. deconstructionism for my academic readers, since I’m a huge social constructionist and find deconstruction to be passably interesting, but I’ll spare you!)

It basically comes down to this: do you want to create or inspire, or tear things down? There’s certainly a time for both, as when tearing down harmful institutions such as slavery or fascist governments, or in times of personal metamorphosis, but I think we need to examine our motivations in which types of actions we begin with. Since I’m folklorist, I’ll remind others: you win more flies with honey than vinegar.