Me performing an American Tribal Style® Belly Dance solo

(photo by Curtis Claspell)

If you haven’t already, go read Part 1 of this post in which I discuss various issues such as the multiethnic/multicultural origins of belly dance, why belly dance has political implications in both the West and the East, and why this is a complicated topic that shouldn’t be handled in a simplistically ignorant and racist way like the original Salon post author did.

Now that you’re caught up, let’s turn to the distinction between cultural appropriation and cultural borrowing. I’m aware that there’s a large body of scholarship out there on this topic, but here I’m relying more on work on privilege.

As I established in my first post, cultures come into contact and borrow from one another. It’s just what they do. Ask any anthropologist, folklorist, or historian, and we’ll tell you that cultures are dynamic rather than static. We’ll tell you about the concept of “invented traditions,” which really applies to every tradition, since they all had to start somewhere. From engagement rings to Thanksgiving dinner, every tradition a culture has got its start at a definite point in time, and from then on accrued meaning and significance to that culture, sometimes to the point of people not being able to imagine life without it. Belly dance is, as you might’ve guessed, an invented tradition. Why it became so meaningful is simultaneously kinda arbitrary (why do some art forms thrive while others don’t?) and also revealing as to the values of these various cultures.

In my mind, the questions we as Western belly dancers should be tackling are: where does belly dancing fall in the borrowing-appropriation spectrum? How does Western (and perhaps, PERHAPS white) privilege play into this? And how can we respectfully listen to the claims of others while defending our rights as global citizens to partake in art forms that appeal to us?

First, I think it’s important to note that appropriation occurs within a power imbalance. There are few components to this:

- When the transferred item or genre is sacred and it is taken out of that context and put into a secular one, we’re probably looking at cultural appropriation, not borrowing. See: appropriation of Native American cultures. (related: Jezebel has a pretty good take on this issue, specifically using Native American examples)

- When the borrowing culture operates on stereotypes of the original culture, stereotypes that are detrimental and affect real people’s lives, we’re probably dealing with cultural appropriation. See: blackface.

- When the borrowed-from culture is a minority that remains powerless politically and voiceless culturally, and thus no reciprocal exchange is possible, we’re looking at appropriation. See: depictions of Gypsies/Roma.

Now let’s look at Westerners who belly dance and see how these criteria fit. First, belly dance is not sacred in most of the contemporary and historical cultural contexts in which it originates (whew, lotta qualifiers there, see how complex this phenomenon is?!). Belly dance is a social dance, performed in various situations by different groupings of people, from informal women-only gatherings, to wedding parties, to formal entertainers in dining establishments. So, I don’t feel there’s any evidence that Western belly dancers are polluting something sacred here.

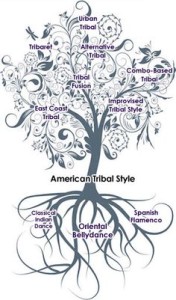

Do Western belly dancers promote stereotypes of Middle Easterners? Possibly. A lot of art involves highly refined aesthetic forms, which do carry the possibility of stereotype and caricature. But that’s one big reason I’m drawn to American Tribal Style® Belly Dance – it’s syncretic on purpose. We’re not trying to emulate any single tribe or culture out there; we’re making our own urban tribe, coming together as a community on our own terms. Our movements borrow from Spanish flamenco and Indian classical dance as well as Middle Eastern folkloric dances. Our costumes draw from disparate cultures as well (including our own – there’re a ton of fabulous body mods to be seen in ATS, from tattoos to piercings), so we’re not mimicking any one existing culture. So tribal and tribal fusion dancing helps me navigate this facet of the issue; I’m not sure how other belly dancers handle it.

Are Middle Eastern dancers helpless and voiceless in this debate? Obviously not, as the original Salon blogger has demonstrated. I hope this doesn’t sound too flippant, but it’s a public part of their culture that they display at home and abroad – if it had been secret, or spiritual, that might have been different. It’s not like we wrested it from their innermost sanctuaries and profaned it by bringing it out into the open. Instead, representatives of these various Middle Eastern brought the dance over to the U.S. (and other countries) when they immigrated here. They shaped it, and continue to do so. They get some of our stuff (like language) and we get some of their stuff (like dance). Is there still a power dynamic? Unfortunately, yes. Orientalism is alive and well. We’re still wading through the effects of colonial powers in the Middle East and the rest of the world. That stuff ain’t fun. But I don’t think learning about another culture through dance is the most offensive thing out there when it comes to navigating these tensions.

…Which brings me to my final point. If you are completely oblivious to the fact that your engagement with another culture could potentially be causing harm (even if it’s simply perceived harm, like emotional upset, without a “real” physical component), then you are operating from a place of privilege. I know privilege can be a sticky topic, but I like these two web comics which demystify it without shaming or blaming. I also have written about privilege and its gendered dynamics here, and how good intentions can still cause harm here.

Okay, back to the intersection of privilege with cultural appropriation! I really like this Everyday Feminism blog post about navigating privilege, in which the author states: “We have a responsibility to listen to people of marginalized cultures, understand as much as possible the blatant and subtle ways in which their cultures have been appropriated and exploited, and educate ourselves enough to make informed choices when it comes to engaging with people of other cultures.”

So, because I recognize that I come from a place of Western privilege and white privilege, I have to acknowledge that maybe my actions are doing harm to others, but that harm is imperceptible to me. I have to admit that I could be wrong, and I have to be open to listening respectfully to the views of those who feel that they were wronged. I have to understand that the negativity is likely not about me personally, but rather the systemic injustices that I happen to benefit from, and which are being repeated in my blithe borrowing without acknowledging the historical circumstances that shape the exchange. G. Willow Wilson asks Western dancers to keep in mind that, when performing belly dance, they have a moral obligation “to look that privilege steadily in the face.” I think that’s a great starting place. But so is a reasoned and researched examination of the issues at stake, which I have tried to provide in this blog post series.

Even with all these factors to consider, I don’t think Westerners performing belly dance is the most egregious form of cultural appropriation out there. I think it is a borrowing and an exchange more than an appropriation. I think there is room for critique, and there is room for positive change. I think the original Salon author is entitled to her feelings (because an important component of recognizing one’s privilege is recognizing that you don’t get to tell other people what they have a right to feel), though I also think she misunderstands the diversity and complexity of belly dance both in history and in contemporary times.

While most belly dancers are, I believe, already engaging with these issues, I’m hoping that it opens the wider public up to these kinds of discussions. I hope they look beyond the harmful “harem girl” fantasy associated with belly dance – harmful to all women, regardless of skin color – to get a sense of the dance’s richness, variations, and textures. Further, I hope that Western dancers will be a bit more thoughtful about what we borrow, and how, and from whom – and also what we give back.