I recently had occasion to celebrate a new article being published, my “Sorting Out Donkey Skin (ATU 510B): Toward an Integrative Literal-Symbolic Analysis of Fairy Tales” (which you can read on the Cultural Analysis website for free). That project has been in the works for a while, over a decade at this point. I thought I’d share not only the link to the article, but also a piece that I wrote to accompany my MA thesis (also on this topic) which I submitted in 2007 as part of my coursework in folklore at Indiana University. It’s more personal and process-oriented than most of my scholarship, so I thought it might be an interesting read. Certainly some of my views have evolved since then, but such is life.

I recently had occasion to celebrate a new article being published, my “Sorting Out Donkey Skin (ATU 510B): Toward an Integrative Literal-Symbolic Analysis of Fairy Tales” (which you can read on the Cultural Analysis website for free). That project has been in the works for a while, over a decade at this point. I thought I’d share not only the link to the article, but also a piece that I wrote to accompany my MA thesis (also on this topic) which I submitted in 2007 as part of my coursework in folklore at Indiana University. It’s more personal and process-oriented than most of my scholarship, so I thought it might be an interesting read. Certainly some of my views have evolved since then, but such is life.

So sit back, relax, and get ready for some vintage 2007 writing.

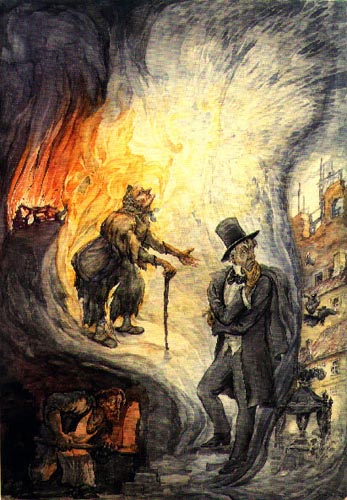

My involvement with ATU 510B, “Donkeyskin,” began in 2002, when I enrolled in Alan Dundes’s “Folk Narrative” class at UC Berkeley, where I was working toward a bachelor’s in folklore (technically, my degree would be in “Interdisciplinary Studies Field” with a concentration in folklore, as there was no undergraduate degree in folklore at Berkeley, just a master’s degree). Professor Dundes gave a lecture midway through the semester about the Electra complex in “Donkeyskin,” which thoroughly infuriated me. Where he saw a psychological attachment between father and daughter in the tale, I saw incestuous abuse. I resolved to write a research paper on the topic, and Professor Dundes heartily encouraged me to do so when I visited him in office hours. Despite my feminist leanings, in that first paper on ATU 510B, “The Problematic Electra Complex vs. Realities of Abuse: Psychoanalytic and Literal Approaches to ‘Donkeyskin’ (AT 510B),” I concluded that psychological and literal approaches to the tale were complementary. In fact, it seemed odd to me that most scholars tended to view the tale from only the one angle or the other, when both approaches had powerful explanatory appeal. This paper is included in Appendix A.

I revisited my research on ATU 510B in 2004. That spring, among the last classes I took at Berkeley were Alan Dundes’s “Psychological Approaches to Folklore” and Andreas Johns’s class on the fairy tale. I expanded my work on ATU 510B, the result being a paper double the length of the first one, titled “If the Interpretation Fits: Psychoanalytic and Literal Approaches to Father-Daughter Incest in AT 510B” (see Appendix B). I referred to more versions of the tale in my analysis, and brought in more theoretical references as well. I also presented my research on ATU 510B at two conferences that year, one version of the paper at the California Folklore Society meeting in Northridge, California in the spring, and the other version at the American Folklore Society meeting at Salt Lake City. I include the latter paper, “If the Interpretation Fits: Symbolic and Literal Approaches to Father-Daughter Incest Fairy Tales,” here as well (see Appendix C).

Those three prior versions of my work on ATU 510B represent different phases of my thinking about not only the tale itself, but also the interpretation process. I started out with the aim to demonstrate that a feminist perspective was necessary to supplement the lacks of a psychoanalytic perspective, but I was unable to completely discard the insights of psychoanalysis, despite its sexist biases. When I began to revise my research, I wanted to explore the spectrum of meanings available within different versions of the tale. I was still interested in the gap between psychological and feminist interpretations, but I wanted to expand the frame of the paper. Hence the shift in the title from psychoanalytic and feminist terms to symbolic and literal terms. The readings I’ve done in psychoanalysis have thoroughly influenced me here, for I first encountered the terms “manifest” and “latent” in psychoanalytic literature. That fairy tales should have both manifest and latent levels of meaning is evident; but how to access these multiple meanings?

Influenced by my classes at Indiana University in folklore as well as gender studies, I began to think about how texts “mean.” Intertextuality, performativity, and other postmodern concepts inspired me to explore the polysemous nature of texts (and also to put more things in the plural and in parentheses than possibly ought to be). I realized that there never was and never would be only one meaning for anything, so why should ATU 510B be treated as a homogenous phenomenon? I also had the opportunity to write articles for The Encyclopedia of Folk and Fairy Tales (forthcoming from Greenwood Press), which, particularly the ones on psychological approaches to folklore, gender, and incest, got me thinking about the frames through which we approach fairy tales.

Like any type of cultural performance or art form with historical ties as well as symbolic content, traditional elements as well as innovative ones, fairy tales fulfill multiple functions, ranging from entertainment and education to political instrumentalization. Fairy tales also provide flexible discursive spaces in which prevailing norms can be debated and alternative identities can be explored. However, fairy tales are also mirrors, to put it simply. I discuss this oft-used metaphor in the “Interpretive Methodologies” section of my thesis paper, for it continues to fascinate me and be useful for thinking. The interesting thing about the mirror metaphor is that it is visually oriented, like much of Western culture, and also that it implies that an objective reality exists, or at least that viewer and viewed, subject and object, are separate. I believe that the prevalence of the mirror metaphor in scholarship is one reason why fairy-tale scholarship has been so one-dimensional, focusing only on one version of a tale, or only on one interpretive frame, and so on. While the mirror metaphor is poetic and can be helpful in explaining why the interpreter or listener or reader of a fairy tale continually sees in the tale what she desires to see, I believe that fairy tales must be approached as more complex than mirrors. Moreover, interpreters must become aware of the perspectives that they bring with them to the interpretive act, for these perspectives may impose a frame upon the materials. This framing process is not necessarily artificial, for fairy tales are multiply framed texts to begin with, but it means that extra caution must be taken if one intends to make theoretical statements about fairy tales.

The purpose of this paper, then, is not only to revise my prior writings on ATU 510B into some publishable form in order to bolster my academic career, but also to get my ideas out there and start some dialogue about how we look at fairy tales (and texts in general). I am excited to get to talk about one of my favorite fairy tales at length, for I take genuine pleasure in working with these materials, but I’m also thrilled at the idea of proposing a syncretic approach to fairy tales that might be interesting and useful to other scholars. This dual purpose—to provide an interpretation of ATU 510B as well as provide a theoretical framework for interpretation in general—was my goal from the inception of this project. However, I have trouble with the revision process, so this project took me longer than I’d anticipated. The theoretical framing of the first few sections was the most difficult; once I got into the interpretation, I was able to coast. A good chunk of this paper is simply interpretation of ATU 510B. I believe that this is as it should be with folkloristic scholarship, for theories without data are just about as unsatisfying as data without theories (channeling Dundes with that statement, perhaps).

Throughout the revision process, I learned about my style of scholarship in an archaeological fashion. The earliest version of this paper was too heavy in quotes and clunky passages, indicating my insecurities as a younger scholar. I sought validation by letting others speak for me, and I hadn’t really found my voice yet. Then, in the second version of this paper, I let my own voice appear more in the text, but I still quoted other scholars quite extensively. I looked for everything that had ever been written on ATU 510B, in part because Professor Dundes had trained us to do exhaustive research on a topic before writing about it in order to avoid repeating what’s already been said, and in part because I wanted to write something authoritative on ATU 510B. Now, I look back and wonder why in order for a paper to be authoritative it must reference everything else on the subject. How much must we demonstrate familiarity with texts within a discipline in order to achieve competence, and by whose standards? Is this an issue of respect towards one’s elders, or is it fueled by a tradition of learning by example? I’m not saying that I regret doing all the reading and synthesizing that I did, nor that scholars should write about a topic without thoroughly researching it first. Rather, I’m wondering why that approach was so thoroughly ingrained in me, and why I clung so fervently to it for so long. I wonder, too, why it was so important to me to write something “authoritative” on a given tale. What baggage comes with the notion of authoritative writing? The attractive position of being an author, surely, as well as being an authority on a subject. But with authority comes the danger of silencing and excluding other perspectives.

This is what I struggle with in regard to fairy tales, and folklore in general: the desire to say something true and important about these texts and phenomena, weighed against the knowledge that truth is relative, everything is subjective, and Western epistemologies for learning and meaning-making are very skewed. I seek validation as an academic—hence my earlier phase of excessive quotation, which I still catch myself doing sometimes—even as I recognize that academic thought is based upon concepts that are grounded in and create historical inequalities, such as Cartesian mind-body dualism, sexism and essentialism, and Judeo-Christian hierarchies. So my work is, in part, about challenging and changing the system from within.

Another aspect of my engagement with fairy tales within academia is the attempt to understand culture and the human condition from one particular angle. As ambitious as I am, I have to accept that I have limits, and I cannot possibly hope to study everything about culture. Instead, I can limit my scope and go deeper into meanings. Fairy tales resonate very deeply with me, and also with the myriad others who read them, write them, and write about them. These transforming and transformative narratives may only comprise one tiny part of culture, a felicitous conjunction of oral and literary traditions and innovations, yet they are also sites where cultural change and conflict, gender issues, and means of production and privilege interact. Fairy tales are artistic expressions of communal and individual concerns, using fictional and formulaic structures, with flexible vocabularies and conventions. For all that they are currently regarded as entertainment in Western cultures, fairy tales are not any less stories about culture and people, with insights into culture and people. What I am trying to express here is my dual frustration at the trivialization of fairy tales and their importance, as well as the trivialization within the study of fairy tales of the significance of certain themes. For example: “What, a story about incest? No, that’s certainly too horrible, it must be a metaphor for something else…” While I’m not certain whether this line actually goes through people’s heads, I suspect that some kind of similar rationalization is put forth for the metaphorization of fairy-tale content. And this question—on which level to understand the content of fairy tales—is one of the central issues I address in this paper.

The fact that fairy tales are generally about individuals within families, whether these families are perceived as real or as symbols for ego-complexes, continues to intrigue me and be relevant to my research. A close friend and I were once discussing why we were drawn to our somewhat bizarre research topics: she to prostitution, and I to father-daughter incest fairy tales. These things were not part of our life experiences, and yet we got something meaningful out of their study. My friend hypothesized that I was so fascinated by the father-daughter dynamic because within a nuclear family unit in a patriarchal culture, the father-daughter relationship is the most asymmetrical. That is, the father has the most power within the family (itself a model for society), and the daughter has the least power. This relationship, then, reflects a tension that resonates with larger power imbalances within societies. And because I am drawn to patterns, to stark illuminations, this relationship entrances me, and compels me to try to explain its presence in stories that have gone through many redactions and guises.

This explanation works, partially. So does the reason that I am drawn to these tales because they were once ostensibly common in the oral traditions of cultures that speak Indo-European and Semitic languages, yet these tales now have been subsumed under their sister tale, ATU 510A, “Cinderella,” in popularity (a topic I address in the paper I will deliver at the American Folklore Society meeting this year). What is going on with father-daughter incest stories, that they ceased to appear in collections of fairy tales and children’s books and movies, but only recently made a resurgence in retellings by modern American feminist writers of fantasy? This reason is the one I give most often to family members and non-academic friends, because I can use a concrete example, “Cinderella,” to discuss the divergences of “Donkeyskin” in oral tradition and literary retellings. Nevertheless, I can only rely on such explanations for a certain amount of validation. It is rather more difficult to provide a satisfactory account of my interest in the tale when my family takes an active interest in my folklore career, and shows up to hear one of my conference papers. This happened at the California Folklore Society meeting in 2004, which was held at Cal State Northridge, of which both my parents are alumni. Since my parents still live in the area, they not only hosted a bunch of Berkeley folklore students for the weekend, but they also showed up to hear my paper on ATU 510B. That was an interesting experience. I felt that I had to act in a scholarly manner, analyzing my material from as detached a distance as possible, in order not to upset anybody or arouse undue suspicion about my attachment to this tale. My parents were, to their credit, not too alienated either by the topic of my paper or by the overly academic, discipline-specific, and jargon-filled approach I took. The processes of meaning-making and revision, then, had different ramifications for this one conference presentation, as I was concerned about how this paper about relationships would impact my own relationships.

Revising my work on ATU 510B for conference presentation was challenging largely because I had so much to say about the tale, it was difficult to fit it into ten pages or twenty minutes, whichever came first. At the same time, that process helped me to cut out unnecessary quotations and synthesize my thoughts in digestible segments. It is difficult to know where to be brief, and where to expand; it is also interesting for those of us who study artistic communication to think about how we communicate insights about said communication. In sum, this project, born of a fascination with a particular story and revised numerous times, represents various phases in my scholarly development but is also marked by my personal life. There are myriad connections between my academic work and the rest of my life, and this is evident in how and why I study fairy tales, particularly how I am drawn to investigate the ways in which multiple meanings can be understood through attention to different layers of the texts.